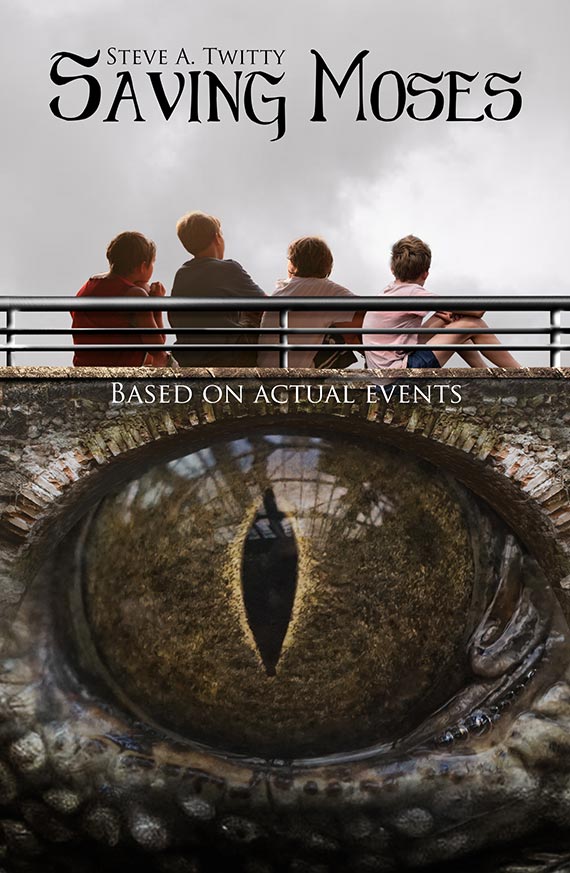

Saving Moses

Based on actual events

Set in South Miami, Florida in the early 1960’s, Saving Moses is based on actual events. The story is about four boys, pre-teens, best friends all, who discover in a canal an old, one-eyed alligator they name, ‘Moses’. The boys unexpectedly form a bond with the old beast. When they learn Moses faces certain death at the hands of two local poachers, the four plan his liberation, not realizing their struggle will end in tragedy.

Overview & Preview

27 Chapters

196 Pages

Like a parent’s love for his or her children, there is often one particular child who holds favor, for whatever reason, and so it is for me and the books I have authored. Terror Beneath the Bayou was a milestone, my first published book and a source of pride and sense of accomplishment. My third book, Betwixt And Between, was fun to write for it allowed my imagination to soar while my latest book, Lady Alone, had me aboard a sailboat once again, if only in my mind. But it is Saving Moses, my second book, that will always hold that ‘favorite child’ place in my heart.

From the time I began writing with intent to publish; see Biography, I knew I would write Saving Moses. The story is based on actual events that happened during an impressionable period of my life when scrub forests and wooded expanses dominated the landscape of Perrine, South Miami, a time of innocence when no one thought twice about their kids playing outside or riding their bikes to and from school. Television was an attraction but not a distraction for with the lure of such wide and wild spaces, the out-of-doors was where my pals and I spent most of our free time.

As for the story itself, I took several liberties to highlight characters’ personalities and set up scenes to move the story with a smooth flow to the tale’s emotional ending. Landmarks like Big Tree and Tarzan Vines were real, as was the canal and Moses, but not so the sugar mill or Dillardtown, the mill’s supposed local community. Yate’s gas station did not exist either, nor did the cemetery. What did exist was the community of Perrine and a neighborhood in which, for a brief moment in time, four boys, bound by an unbreakable friendship, dreamed up adventures that continue on as fond memories.

It is my sincere hope this glimpse into the past will be an enjoyable read of a snippet of life and friendship in the early 1960’s before computers became king.

CHAPTER ONE

“It was the summer of 1961 and maybe we were a little rambunctious

at times but we were kids, doing what kids our age were supposed to do …

Only, kids our age weren’t supposed to die.”

– Milton Marshal

Present Day

A late model Ford Escape with Florida license plates dodged potholes as it drove north on Sugar Mill Road, a crumbling macadam cut through South Florida scrub of weedy hardwoods interspersed with stood of spindly pines, scrub oak and patches of saw palmetto. The vehicle rolled past three rusting oil drums on the right that blockaded an entrance to a rutted dirt road and a mile further on, stopped at a T-intersection with Eureka Drive, another macadam road running east from Sugar Mill Road. Eureka Drive extended straight as a die through the tangled lowland where it passed between guard rails of a pipe bridge spanning Black Creek canal before becoming lost by distance and greenery.

Set at an acute angle across the intersection from the SUV were the four crumbling walls of a single-story structure on an acre lot overgrown with grass and weeds. A half mile beyond the derelict building, Sugar Mill Road dead ended at eight rotting railroad ties blocking access to the sagging gate of the rust-streaked hulk of a sugar mill abandoned decades before.

Sixty-eight year old Milton Marshal rode shotgun in the vehicle’s passenger seat, squinting from the relentless mid-morning sun. Balding and thin in stature, he sported a two-inch scar angled across the bridge of his left cheek, long ago healed. His pensive silence during the two hour drive across the Sunshine State from Naples to Perrine had been something his daughter, thirty-seven year old Marsha Cohen, the car’s driver, had expected. Her father was returning to the town of his youth, a last chance to visit a place pivotal in his life before developers had wiped away all traces of whatever might still remain and long before this trip had started, Marsha had sensed her father’s

apprehension about going.

Seated on the vehicle’s back seat and as quiet as their grandfather were Marsha’s two children, Deacon, eleven, cradling a drone on his lap and busy thumbing the controls of a digital game on his i-phone, and Dorthy, fourteen, her attention on the wilderness beyond her window.

Marsha motioned toward Eureka Drive, concerned her father may be lost, especially since Sugar Mill Road dead ended. “Should I turn here?” “Keep straight,” Milton instructed. He pointed to the abandoned structure across the intersection. “Stop in front of that old building. That’s Yate’s.” He said this with astonishment that some remnants of the building were still there.

Seeding grass and woody weeds had taken over the gravel drive of what used to be Yate’s filling station. The harsh South Florida sun had all but obliterated the stenciled, green letters, Yate’s Gas and Garage, from the ruin’s facade. Gone were the twin gas pumps which once stood on the now weed-ringed concrete island. Missing in action were the Vendo Coca Cola machine alongside the cramped office’s shattered glass front door and the “SINCLAIR” sign which had perched atop the bay roof over the service area. Anything of value appeared to have been carried off decades ago leaving only roofless walls and memories.

“Back in the day,” Milton reminisced, “Yate’s was the only place in Dillardtown to get gas.”

“That’s a dumb name for a town,” commented Deacon. He raised his head long enough to take in the dilapidated structure, having no interest in history, before turning back to his game. He had his mother’s brown hair and brown eyes that showed his impatience when things bore him, like riding in a car for hours to some no-where place on the opposite side of the state, far from his friends. He had agreed not to complain when his mom promised he could bring his drone and he was more than ready to get it airborne.

Milton eyed the assemblage of rusted metal a half mile ahead where three shifts of workers had once produced two hundred tons of sugar a day. The factory’s great smoke stack that used to belch a never-ending column of smoke rich with its sickly sweet smell of raw sugar had collapsed through the roof of the processing plant while loose panels of sheet metal on a rotting warehouse swayed in the morning breeze as if bidding farewell to better days. “Dillard Sugar built Dillardtown for their employees,” Milton explained to Deacon. “That’s where the name comes from. My father worked there.”

“How long ago did you live here?” Dorothy asked. She had sandy blonde hair with hazel eyes and was as ready as her brother to get to where they were going, hopefully somewhere with as much wilderness as here. This place had to have been teeming with reptiles.

“My dad got a job here after the war, just after he and mom married. I was born in nineteen fifty.”

Deacon’s impatience was killing him. “When can I fly my drone?”

“Don’t interrupt,” Dorthy scolded her brother who scowled back.

“Go to that next road, on the right,” Milton told Marsha, referring to yet another T-intersection a hundred yards ahead and marked with the rusting remains of a sign which once read, Welcome to Dillardtown. “That should be the entrance into the old neighborhood.” He looked over his shoulder at Deacon. “I’m sure there will be plenty of space to fly your drone.”

Marsha turned onto the decaying concrete road leading into what had been Dillardtown and Milton’s shoulders slumped at the total desolation. He had spent two days with Marsha and her

children in their Naples home before they had set out on this trip earlier that morning and during his time at her home, he had refrained from viewing the old town on Google Earth. He had already learned of the property’s pending development but he had wanted to cling to a sliver of hope something still remained of a place which had created and then changed not only his life but that of his three best childhood friends. Seeing reality, disappointment drew long his face. “Stop here,” he whispered in a tight voice to Marsha.

She halted within the shade of a ten by twenty-foot sign erected on the edge of a seventy foot wide strip of thick, matted grass between the road and a sagging wire fence separating the town from the tangled scrubland from which the community had risen. This newer sign was emblazoned with the words; Future site of Sunshine Estates and Shopping Mall and depicted a young family of four smiling happiness in the front yard of their heavenly home with its spacious garage and easy shopping in the background.

What remained of Dillardtown was a grid of crumbling streets creating sixteen rectangular blocks, each with five disintegrating driveways on their long sides leading to alternating two and three bedroom, cloned slabs of terrazzo flooring and surrounded by unattended yards, hedges and once decorative shrubs all gone feral. The original perimeter roads had been named for the four cardinal directions and formed a square around the community with an extension of South Street as its entrance, where the SUV was. On the far side of the abandoned community heavy machinery had been assembled; yellow bulldozers, giraffe-like steam-shovels and two rows of dump trucks

ready to haul off the last vestige of a town bittersweet to Milton.

Dorthy leaned in between the front seats. “Where was your house, Grandpa?”

“Are we getting out?” Deacon moaned. He stashed his phone in his shirt pocket and fingerspun a propeller on his drone.

Milton unlatched his seat belt. “I’ll show you around,” he told his daughter and pointing the short distance to an intersection on the left, he answered Dorthy. “That’s West Street, my street.”

Deacon bailed with his drone. He jogged to where West and South streets met and as he swept away loose gravel with the side of his joggers for his launch area, Milton led Marsha and Dorthy down West Street, between the silent remains of houses that had once been part of the thriving community. He stopped in solemn silence in front of the third house on the left, as if visiting a funeral home. Marsha gave Dorthy a stern look, a warning to keep silent while her grandfather reconciled a past he had rarely mentioned and never discussed.

“You know,” Milton said softly after a long moment of reflection, “I didn’t even have my own bedroom.” This was said as if after all these years this fact just occurred to him. He looked at Marsha, astounded. “Imagine that.”

“Where did you sleep?” Dorthy asked.

“On a roll-away bed in our living room.” This was said more as a bland statement than with any emotion. “My father was a collector, or so that’s what he had called himself. He kept all of his

junk in what would had been my bedroom.”

“Wow,” Dorthy commented at what she saw as a violation of civil rights.

Milton shook his head in memory. “You didn’t ask my father the why’s and wherefore’s. You did what he said.”

The hum of Deacon’s drone going aloft drew Milton’s attention toward the whir of propellers. He spotted the aircraft in the cloudless sky. Returning to his tour, he led his audience two lots down. “This was where Floyd Raines lived. We called him, Chester.” He smiled at the memory. “Floyd had polio when he was about five which had left him with a limp.” Figuring Dorthy and maybe even her mother were not familiar with the significance of the term, Milton explained. “Back in the day there was a weekly TV show, a western called, Gunsmoke. I think you can still get it on reruns. When the show first aired, the sheriff’s deputy was named Chester and he had a limp.” Milton chuckled. “Floyd hated that name.”

Deacon’s drone passed high over their heads and shot off toward the heavy earth-moving equipment. Working the controls with thumb and finger, he shifted his focus between the drone’s computer screen and the path to join the others.

Dorthy called to her brother. “You’re going to lose that thing again if it goes too far.”

“You mentioned before there were four of you,” Marsha said, sensing talking about his past was helping her father beat back emotions which could turn this into an untenable experience for him.

“The other two were Mark Donado and Davy Duncan. We called ourselves, the Four Musketeers.” Milton’s smiled betrayed fond memories tinged with regret. Catching himself, he shook off his feelings.

“Did Mark and Davy live here too?”

Dorthy asked. Milton motioned to the east. “Two blocks that way. Davy lived on one corner and Mark behind him, on the other.”

Deacon brought his drone back and hovered it over their heads. The four-prop aircraft automatically made slight adjustments in pitch, obediently holding a set position in an erratic breeze. He tilted the drone’s control screen so his grandfather could view it. “This is us.” He pointed to four figures as seen from a height of three hundred feet.

It took Milton a moment to assimilate the full picture; Marsha’s shaded car, a snippet of the perimeter fence and the checkerboard-like layout of home sites. Separated from the main community were the remains of five homes at the lower end of the grassy strip along South Street. These larger structures, residences of the sugar mill’s upper management, had terrazzo flooring a third larger than the town’s other homes and their own swimming pools, now brown patches of dirt.

Milton focused on the aerial view of his home’s driveway linking street to a concrete garage floor clipped to the head of white terrazzo laid out in an inverted L-shape. Internal wall foundations demarcated a combination living room/dining area with a small but adequate kitchen which opened into the garage. The L-shape’s foot was laid out in a short hallway connecting a compact bedroom to a marginally larger master bedroom at the toe. Between the two rooms, on the opposite side the hallway, was a shared bathroom.

Thankful some remnants of Dillardtown still remained, Milton was curious. “How high will that thing go?”

“How high do you want to go?” Duncan asked, happy to oblige. “It’s at three hundred feet now.”

“What I’d like is to look out that way.” Milton pointed toward the scrubland to the south. “That’s our old stomping grounds and I’d like to see what’s left of it.”

Deacon fingered levers and the camera shifted angle as the drone gained altitude, widening the vista across a half mile of scrubland to the thin thread of Eureka Drive and gray lines of the bridge’s guard rails. Five miles further south was a horizon of modern office buildings. “Four hundred feet,” he told his grandfather.

Milton studied the drone’s computer screen, again seeing Marsha’s car, the grassy strip and leafy bushes along the straight edge of the fence but at the higher altitude. Thick were stands of woody weeds interspersed with dark shapes of saw palmettos and patchy pine thickets. He touched the screen at a point within a rocky clearing in the scrub fifty yards behind the five managerial home sites. “There used to be a banyan tree right here. We called it, Big Tree. It’s where we had our tree house.”

“You mean a strangler fig?” Dorthy asked her grandfather.

“Yes, I believe that’s another name for it.” Milton paused and added with disappointment, “Looks like it’s gone.”

“Back then, was it all grown up like it is now?” Dorthy asked, referring to the expansive forest.

“Yes, it was.” Milton’s eyes flashed memories of adventures and a raw education of reality.

“Did you ever catch any snakes?” Dorthy asked with spirited interest.

“Davy was the snake catcher,” Milton replied. “If it crawled, Davy could catch it.”

“Don’t get any ideas,” Marsha warned her daughter. “You’re not going to traipse around in that jungle and we’re not taking anything back but ourselves.”

“Oh, mom,” Dorthy moaned. She didn’t come all this way to not wrangle up a reptile of some sort. She parted tall grass along the road with her foot and failing to flush out anything of interest,

moved up Floyd’s home’s rotting driveway, on the hunt.

“Don’t go far,” Marsha told her daughter.

“Deacon, can you take your drone up a bit higher?” Having broken through a thin layer of proverbial ice, Milton felt up to sharing a bit more about a part of his life he had silently struggled with all these years.

Deacon made an adjustment and the scene on the ground fell away. “Six hundred feet.”

Milton tapped the screen, this time closer to Eureka Drive and the bridge, pointing out a football field-size leafy clump of three massive banyan trees close to the road and appearing as a dark green cloud topping the undergrowth. He smiled relief. Not all of their old haunts had been lost. “See these trees? That’s Tarzan Vines. It was one of our hideouts, especially from Randy King.” The mention of that name gave Milton pause. It’s a name he wished he could forget but knew he never would. He pushed through his emotions. “He was the neighborhood bully.”

Dorthy rejoined the group, empty-handed but still on the lookout.

Milton traced his finger on the drone’s control screen from Tarzan Vines to Eureka Drive, fifty yards further south, and then two hundred yards east along the road to the bridge and the dark water of the canal. “This is Black Creek canal. We used to go swimming there.”

“Yuck,” Deacon glowered. “You swam in a canal?”

“Awesome,” Dorthy beamed.

“That’s where we found Moses.” Milton’s voice suddenly dropped off as a darkness overcame him. He stepped back from the drone’s screen and looked south as if he could see every ripple on the canal’s water, every rock along its fringe and then his lips tighten in frustration. He hadn’t intended to veer off the planned path he had so meticulously worked out, a path which would have taken things one manageable step at a time, allowing him to reveal his past in a way that was not overwhelming for him or, he was afraid, disappointing to his daughter. But now, the gate was open and he was far from certain he could pass through unscathed for there were questions he didn’t know if he was ready to answer.

Marsha, always attentive to her father’s demeanor, sensed whatever his reasons for coming here, he had reached his limit. “It’s getting a bit hot standing out here,” she commented, looking at her watch. “And it’s close to lunchtime. Why don’t we find a place to eat?”

Deacon’s eyes lit up. “I’m starving but can we come back so I can fly my drone again?”

“I want to look around some more,” Dorthy added.

“We’re coming back after lunch,” Marsha reminded the kids. “Your grandfather still has to meet up with some people later this afternoon, so you’ll both have plenty of time for all that.”

The troupe returned to the car and left Dillardtown. Marsha drove past Yate’s gas station, through the intersection with Eureka Drive and the five miles of bad road to the bustle on Dixie Highway, stark contrast between what had been and what was.

0 Comments