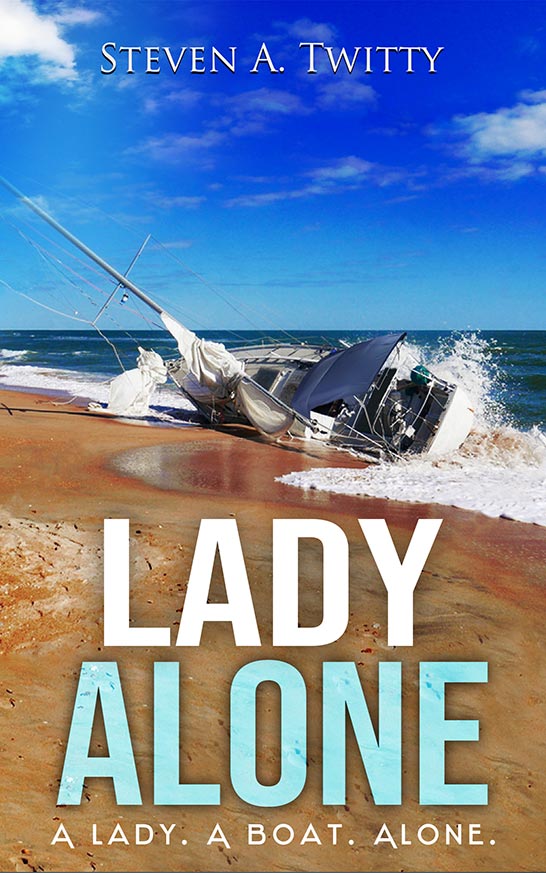

Lady Alone

Lady Alone is a ‘must have’ addition to any adventure library, a tribute to those souls who have overcome fear and persevered through deteriorating calamities far beyond their limits.

Overview & Preview

Joan Mackland, a twenty-three year old Kiwi with no previous sailing experience, makes a bold statement of independence by accepting a position as sole crew on a forty-foot sailboat named, Atmosphere. The sloop is captained by Wayne Yao and is bound from Guam to Hong Kong.

On the high seas, life on board Atmosphere quickly becomes routine but when a nighttime storm in the middle of the Western Pacific Ocean incapacitates Joan with mal del mar the unimaginable swings down from the yardarm. The captain is lost overboard in the storm, throwing Joan headlong into a week of search and survival made more untenable by rookie mistakes that all but doom her and the boat. Near death and out of options for ever finding the captain, Joan is shipwrecked on a deserted island where a local fisherman finds her but rescue does not always equate to salvation. With the sailboat’s captain missing and contraband discovered on board by authorities, Joan’s freedom lies in a man she has never met.

I started sailing in the 1970’s and the boats I have owned since then include an O’Day 23 that I sailed on Chickamauga Lake, Chattanooga, Tennessee, a Cheoy Lee 36 that I owned in Singapore, a Cygnet 20 I owned in Australia and my last boat, a Crealock 36 which I slipped at a marina in Phuket, Thailand. I am far from an expert sailor. I leave that distinction to sailors like Captain Dave Sellers of the sailboat, Nimbus, the late Larry Rutledge of the sailboat, Brisa Del Mar and Don Wagner of the sailboat, Emma Blu’, the Crealock 36 that I purchased.

It was among these sailor friends and other acquaintances that I heard a supposedly true story about a woman, I named, Joan, who had the great misfortune of finding herself alone on a forty foot sailboat after the captain was lost overboard during a storm in the middle of the Western Pacific Ocean.

Such a scenario is certainly possible. Situations at sea can easily deteriorate with little more than a whispered warning but what caught my attention about this story was that the unfortunate woman had no previous sailing experience, zilch, and that opened the potential for any number of twists and turns as a dilemma turned into a life threatening crisis.

With the story’s premise on paper, I created a lengthy outline of predicaments that have befallen myself and sailors I know or have heard of, mistakes and oversights that can turn any situation into a nightmare, making it clear that my main character was in for a really rough ride.

One scene that gave me the willies and still does is when Joan is forced to don skindiving gear to free-up the boat’s fouled propeller. I have a serious aversion to sharks and for water so deep it is a forever dark, navy blue and honestly, I don’t know where Joan found the courage to leave the safety of her boat. I’m not sure if I could have pushed aside my phobias to resolve the problem as she did but one never knows until faced with a reality that requires action.

The original ending of Lady Alone is when Joan is rescued, an ending that to me felt too abrupt and incomplete. My editor, Tom Ehrhart, and I went around in circles about this and after due consideration, I added her plight on land, bringing what I believe is better balance to an emotionally satisfying ending for Joan and the reader.

Chapter One

The outboard’s tinny whir rose an octave as it accelerated the wooden fishing skiff away from an exposed sandbar connecting a low-lying, rocky islet to the lower end of a larger, densely forested island. The uninhabited island was a mile and a half long, a third as wide with an unbroken, white sand beach lined with coconut palms crowned with their feather-like leaves, tight clumps of green fruit and trunks leaning as if the winds that sculpted them were still blowing.

Tangled jungle pushed hard up against the frontline defense of palms, spilling out onto the beach as if anxious to claim more of the island. Overhead, frigate birds circled in a clear mid-afternoon sky.

Clipped to the island like a necklace was an oblong atoll, extending four miles, north to south, and a third this in girth. A plethora of corals forming the impressive ring brimmed vibrant colors, beautiful and alluring but bristling with certain destruction for any sea craft venturing too close.

The fifteen-foot skiff skirting the atoll was a veteran of the sea, varnished by sun and brine to a dull gray covered in a patchwork of green paint more stubborn than time and abuse. The boat carried a seasoned, earthy smell of soured netting, stale, sulfury salt and every fish landed.

Bilge water sloshed in the boat’s stern forming shallow eddies around a six gallon, red plastic carboy of gasoline into which the outboard’s fuel line was plugged. Between the rear and middle seats were a gallon-size, aluminum cooking pot repurposed for bailing, a tattered athletic bag and a cobbled together wooden box looking every bit as abused as the boat but still capable of holding an assortment of fishing hooks, lead weights and three monofilament hand lines wound onto red, plastic grips. A neatly folded casting net lay atop a sheet of canvas alongside a galvanized bucket half-filled with today’s catch; three yellow and black rabbitfish, a blue unicorn fish and one green and yellow parrot fish. At the boat’s bow was a four-hook Grapnel anchor on fifty feet of hemp anchor rope.

Atea Napil, a thin, ancient-looking fisherman with Polynesian features sat on the vessel’s rear seat, gripping the outboard’s tiller with a knobbly, callused hand. His wrinkled face looked like a map of the ocean’s currents, toughened, like his boat, by weather and brine. He was clad in a faded blue, long-sleeve shirt and knee-worn, brown slacks, no shoes. From under his fraying straw hat that looked like an unfinished basket, his mottled eyes, white with pterygium, looked back over the boat’s stern to a forty-foot sailboat foundered on the island’s white sand beach, a victim of the latest storm, one day past.

Atea’s eyes followed two side-by-side sets of footprints in the sand left by his own steady gait and the second, stumbling, struggling, both leading from a wood and sheet metal shed at the island’s near end to keel marks on the sandbar where he had landed his skiff.

Skillfully guiding his vessel within calm water close to the outside edge of the atoll’s gnarly coral, Atea twisted hard the outboard’s throttle for all the power the old motor could offer. Glancing across to the atoll’s opposing side, he perused a natural gap in the reef through which tidal water ebbed and flowed. This had been where the grounded sailboat had entered the ring of coral and strangely, its bow-mounted anchor had not been deployed. What the captain had been attempting was not clear to the fisherman but had the fiberglass sloop made good another twenty-five miles south, it could have escaped the storm’s fierce winds by tucking into a safe anchorage.

Atea refocused on his unexpected passenger seated on the folded fishing net, facing him. The frail-looking woman’s eyes were closed, each labored breath rocking her drooping head. She wore khaki hiking shorts and a soiled, gray T-shirt featuring the depiction of a straitjacket. She clutched the fisherman’s half gallon ‘Hello Kitty’ thermos of water as if to lose it was to die. Her blonde hair was matted against her head and her craggy face and body were drawn tight by dehydration. He guessed she was in her twenties but adversity had made her look older than him.

The woman’s shaking hands raised the thermos to her sun-cracked lips. She choked down a swig of water, grimacing as if swallowing broken glass and finding pleasure in doing so. Her eyes opened. She had a dead stare.

It was under the dull white ball of the midday sun in a hard blue sky that Atea had spied the beached sailboat and what he would find to be an incoherent woman sprawled on the sand at the island’s lower end, near a storage shed he shared with two other fishermen.

In a rush to reach the unconscious woman, Atea had purposely run his boat’s bow onto the adjoining sandbar near the motionless body and hurried to what he had figured was a victim of the shipwreck. Helping the gal to her feet, he had shouldered her weight down the beach to his boat as she struggled with every step in desperate need for water, food and medical attention.

“Is there anyone else with you?” he had asked as he seated her on the folded casting net, her back against the middle seat.

“No,” had come the almost inaudible reply.

“What port are you out of?” he had asked, curious of a deprived condition that bespoke of a struggle substantially longer than if the grounded sailboat haled from one of the local marinas on the main island.

As he motored his skiff south, down the length of the atoll and toward his home port twenty-five miles distance, his eyes moved from the sailboat to his shed. He had not seen any indication there had been others on the boat and had not taken the time to check further. In this woman’s dire need for medical care, that search would have to be arranged by the authorities.

“My name is, Atea.”

He caught his passenger’s vacant eyes.

“What’s your name?”

The question echoed in her muddled brain as if within a grand hall emptied and abandoned.

“Joan. Joan Mackland,” she managed. Her body was responding to what little moisture she had consumed from the jug, thinning the fog shrouding her brain. Taking another sip of water, she rolled the moisture in her mouth with her swollen tongue and swallowed. Her eyes drifted out over the skiff’s stern, past her savior at the tiller and to her sailboat beached and abandoned. A morose feeling of deserting a friend came over her.

Atea smiled affirmation to Joan that she would be all right, figuring she needed the encouragement. He transferred his hat onto her head.

“What happened, Joan?” he asked over the shrill of the outboard.

Atea’s question crawled into Joan’s mind and sparked a memory that dispersed the haze shrouding her thoughts, like a wind-blown morning mist, revealing a montage of the prior two weeks that began with great expectations for a distant landfall and in an instant had dissolved into a harrowing struggle for her life.

——————–

Savoring the last sip of her Starbuck’s latte, Joan dropped the spent paper cup into an empty, reinforced corrugated shipping box labeled; Mackland Gallery, 105 Kitchener Street, Auckland, New Zealand. She had arrived at her Uncle Phil’s high-end art gallery earlier that morning to unbox and inventory his latest deliveries, something she had helped with since she had moved to Auckland four years earlier. Having recently completed a university degree in art history, she planned a career in museum administration.

Joan stepped back and took in the paintings she had already unpacked and placed on display racks, a variety of original paintings from as many artists, additions to those hanging on walls or seated proudly on their own display racks organized in two central rows.

Beyond the artwork a wide display window created its own work of art with a view of arboreal Albert Park and on the shop’s glass-paned front door, a Valentine heart hung above stenciled words of the shop’s name and address.

For the last few years Joan had celebrated Valentine’s Day with friends by touring wineries in Northland and Gisborne but this year she had opted for an opportunity to put problems at home behind her for an out of character adventure on the high seas before settling into the more mundane affair of seeking employment.

From her jeans’ back pocket, Joan withdrew a box cutter and thumbed out its razor blade. She cut the plastic straps on the last box of newly arrived stock and laid the knife aside. From the two by three foot shipper she lifted out a single, canvas painting framed in carved mahogany. The work’s subject matter pulled her face tight with a smile; two Spanish galleons and their crews being swept over the edge of the world.

“Uncle Phil,” she called, “don’t say anything to mum about this one.”

Phil Mackland, a pear-shaped man in his mid-forties, also clad in jeans but with balding head, stepped from a rear storage room, a steaming cup of tea in hand. He grinned satisfaction at the artwork his niece held.

“Wonderful,” he said. “It arrived.”

He took a sip from his cup and set it on a paper-cluttered desk at the back wall. Accepting the painting from Joan, he held it out like a doting father with his first newborn. He placed it on a vacant display stand.

“This is an original Ed Miracle,” he declared proudly. He pointed to a caption engraved on a brass plate fixed to the frame below the painted scene, ‘I TOLD YOU SO’, before tracing with his finger the two ships’ inevitable plunge over the edge of the world. His eyes shifted to his niece.

“Don’t worry about your mum,” he promised with a flick of his brow. “Not a word from me.”

His late brother, Joan’s father, had invested in the art gallery years before when it was only an idea on paper and after his untimely death, his widow, Joan’s mother, had inherited his part of ownership. A demanding woman of her husband, that albatross had fallen squarely on Phil, burdening him with her weekly phone calls for sales data and new additions to their inventory.

Uncle Phil’s brow rose. “Since I haven’t heard from your mum about your plans, you obviously haven’t told her. Am I right?”

Joan made a pained face. “Well…” she stretched out the word. “I did mention it to her.”

Uncle Phil’s mouth drew into a thin line of disappointment. “You mentioned it, as in, ‘This is what I’m going to do.’?

When Joan’s eyes fell to the floor, her uncle knew how that conversation had gone.

Phil understood Joan’s deeply ingrained trait of avoiding confrontation, especially with her mother. His late brother’s wife was a self-focused, hard-boiled woman near impossible when she disagreed. She had perfected the art of manipulation, a first-class narcissist, using pity to make her seem the victim in order to satisfy her own emotional needs. It was behavior she had used to box-in her late husband and still used to control her daughter.

Phil admitted he had been surprised when Joan had found the strength to talk her way past her mother’s frustrating conduct when she moved from Christchurch to Auckland for university. At the time, her mother had been squarely against the move, even demanding that he, Phil, talk some sense into his niece. Fortunately, Joan had, for once, held strong and in the end, her mother, seeing her usual tactics had failed, had agreed to let her daughter leave the nest but not without a caveat that Joan owed her for this one. As for Joan’s current plans, there was no way her mother would be willing to permit her only daughter to go so far afield on such an outrageous excursion.

“I know I should have been more firm,” Joan lamented with a sigh. She pulled herself up straight as if suddenly becoming a new person. “When I talk to her later today, I’m telling her exactly what I’m going to do and nothing she says is going to change my mind.” This was said more as a pledge to herself than a promise to her uncle.

“You remember your own words,” Uncle Phil said. “Don’t let yourself down.”

Joan appreciated her uncle’s support and concern. Ending up like the ships in Mr. Miracle’s painting would be a blessing compared to living with the knowledge she had failed to take a major step in affirming her claim of independence with this grand statement.

Phil was not convinced his niece could hold strong with the coming onslaught and as he set the empty shipping box by the desk and picked up his cup of tea, he gave her a fatalistic face. “This could finally end her hold on you.”

He caught Joan’s stare. “Do you have your plane ticket?”

“I have until five this afternoon to pick it up from the travel agent.” She looked at her sports watch. “In fact, I better get going.”

“The only person who can make this happen is you,” Uncle Phil stated affirmation. “You are in control. Don’t forget that.”

“I know I am,” Joan said with a glimmer of a smile. “This is something I have to do and I’m going through with it.”

Phil hugged his niece. “You be careful. Don’t worry about your mum. She’ll get over it. And have a wonderful experience.”

——————–

Atea scooted his skiff past the atoll’s lower end into open water where the ocean’s floor dropped off, changing the water’s aqua-blue color to an almost purple hue. The skiff rode on the backs of a short chop, the waves bobbing the boat as if tapping to a song’s steady down-beat. The rhythmic motion swirled Joan’s thoughts back to her present condition, far from her mother in Christchurch and far from her life in Auckland.

She raised the thermos to her lips, took in one more sup of water and snagged another thread of events that had brought her to the edge of disaster.

The image before Joan was herself driving her blue VW Beetle across Auckland’s Harbour Bridge on her return trip from downtown Auckland to her apartment in Birkenhead. The vista to her right took in a tight gathering of sailboats docked at Westhaven Marina, at the south end of the bridge, while a dozen sailboats scooted about Waitemata Harbour on a summer northeasterly, all set against a backdrop of Stanley Point, North Head Peninsula and farther out, the lone peak of Rangitoto Island.

Joan touched a plane ticket atop her black backpack on the seat next to her, a tangible token of her self-imposed hegira far beyond her own comfort zone. Having never been on a boat in the open sea was cause enough for apprehension but her long time friend and experienced sailor, Lois Tomblinson, was going which dulled the teeth of the unfamiliar. Even with the reassurance from her late father’s brother, she had stepped into the travel agent’s office with nervous anticipation only to have the table turned vertical.

“Hi Ms. Millwright,” Joan had said to the travel agent, “I’m here to pick up my plane ticket.”

Sally had given her customer a bewildered stare and leaned back in her chair. “Have you not spoken with Miss Tomblinson today?” the travel agent had asked. “She had a change in her plans and your trip has to be cancelled.”

The agent was a big-boned woman with short, curly brown hair and pale skin contrasting blood-red lipstick. The nameplate on her desk read; Sally Millwright.

Joan stood as stark as stone processing the information. “Did she say, why?” and before Ms. Millwright could respond, Joan placed her hand on the travel agent’s idle phone. “Can I use your phone? I need to talk to Lois.”

“Of course,” the travel agent had replied. She had nudged the telephone in invitation and busied herself with pending files stacked on her desk.

Punching out a phone number she knew better than her own, Joan’s eyes had stared a hole in the phone’s body, her anger gnawing within her as she had waited through ten anxious rings. When the phone’s message mode clicked on, Joan coaxed the recording to run faster and then said with intent, “Lois, I’m at the travel agent’s office. What’s this about the trip being cancelled? I didn’t go through all of this planning with you just to end up staying here. I’ll call you again when I get home but as far as I’m concerned, I’m still going, whether you are or not.”

Joan cradled the handset, taking a moment to consider what she had just told her friend. Her declaration had been made in the heat of anger and disappointment but as preposterous as that proclamation had been, it seemed to tick all of the boxes for what she truly wanted.

Ms. Millwright, caught between astonishment and awe, had waited for instructions.

“I’ll need my ticket,” Joan had stated with no hint of apprehension.

Ms. Millwright had slipped a ticket from a file and handing it to Joan, she had said, “One way to Guam.” Pausing, she had added, impressed, “I must say, you are a very brave woman going on a trip like this by yourself.”

Joan saw an opening in traffic and worked her VW to the Harbour Bridge’s far left lane. Pushing aside her reflections of how she had reached this point and her pending phone calls to Lois and then her mother, she turned up volume on her car’s radio. The station’s current event segment was in progress.

“…pioneer in life raft design, Steve Callahan will be interviewed on One ZB’s Monday morning show, sixteen February,” the dee-jay announced.

“Mr. Callahan is the author of Adrift: Seventy-Six Days Lost At Sea, the true story of his survival in a life raft after his sailboat struck a whale and sank. Don’t miss what will certainly be a riveting show. And now, a One ZB sports update.”

Joan lowered volume as a jab of uneasiness tightened her stomach, not because she would be four thousand miles away on Monday and would miss the interview but because Steve Callahan, an obviously experienced sailor, had lived through her own worst nightmare; the sinking of the boat he was on, and now, she had whales to worry about. Her jaw tightened at a danger she had not anticipated.

“I hope that was just bad luck,” she commented to the radio’s dee-jay of Mr. Callahan’s ordeal. Surely, nothing like that could happen to the boat she would be on.

2 Comments

Submit a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Intrigued. Can’t wait to read

Davy Jones

An exciting sea going saga about an inexperienced but brave and spunky gal out to prove herself to the world as well as herself. She succeeds to my great disappointment as her success means she avoids going into my, Davy Jone’s himself’s locker